5 Things You Didn’t Know about William Blake,

England’s Famous Romantic Artist

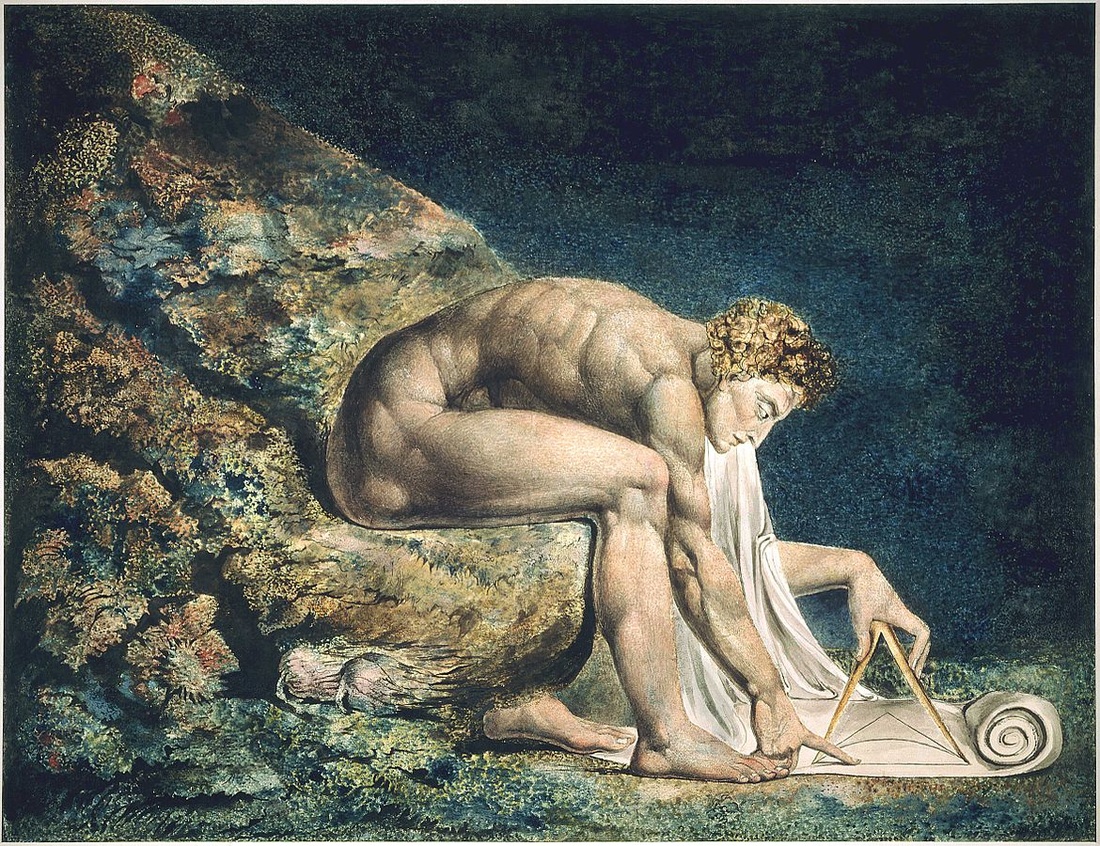

William Blake, Newton, 1795-1805. Collection of Tate Britain. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Mythologized as a madman, the English Romantic artist and poet William Blake most likely suffered from mental illness. Though unstable, he was far from “insane,” as his contemporaries often described him. Yet it’s his eccentric character, along with his visionary poems and prints of an alternate reality, that has long fueled interest in his work across artistic spheres, from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to rock ’n ’roll and graphic novels. A nonconforming radical, Blake believed more than anything in the power of imagination. “The Imagination is not a State,” he once wrote: “it is The Human Existence itself.” Here are five things you may not know about William Blake.

He experienced his first vision at the age of four.

Blake was born at the outset of the Industrial Revolution in humble circumstances above his father’s hosier shop in London, living nearly his entire life in the capital. He was only four years old when he saw God’s head appear in a window—the first of many visions he would recount “in the ordinary unempathetic tone in which we speak of trivial matters,” according to his friend, journalist Henry Crabb Robinson. “Of the faculty of Vision….He thinks all men partake of it, but it is lost by not being cultivated.”

Such cultivation, in Blake’s eyes, was impossible under the constraints of formal education and organized religion. Like many working-class children of his time, Blake was home-schooled by his mother. He would later acknowledge that this upbringing allowed his creativity to flourish, writing in one of his poems, “Thank God I never was sent to school / To be flogged into following the style of a fool!”

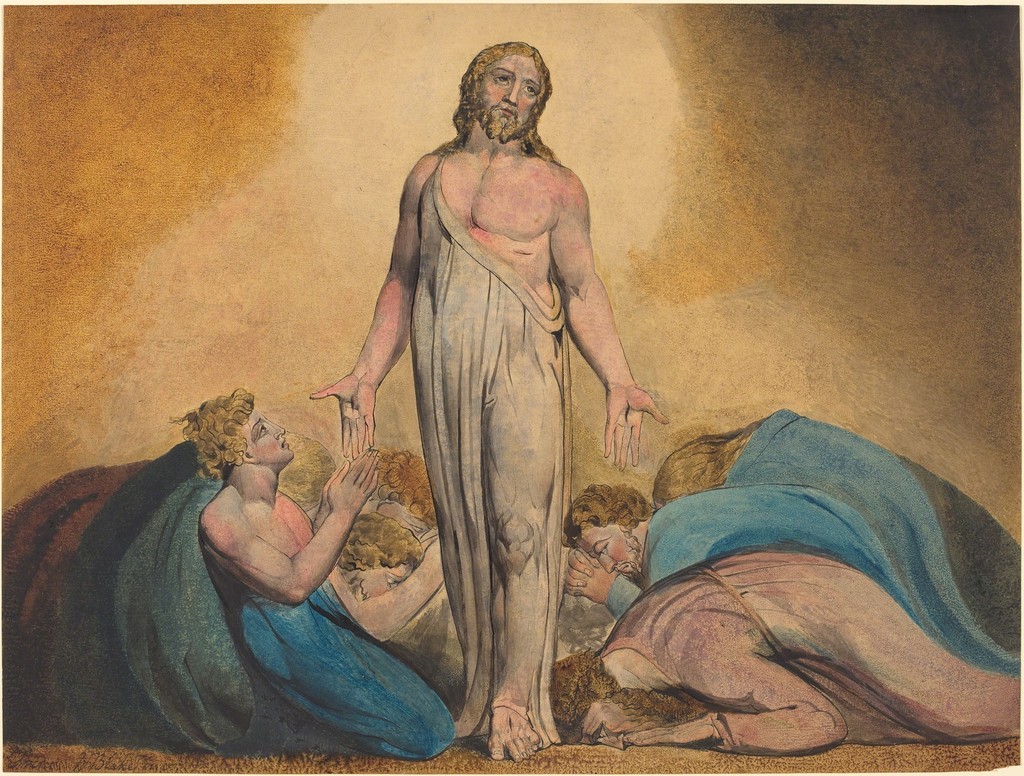

Religiously, he was profoundly influenced by his father’s faith, Swedenborgianism, a cult sect of Christianity that rejected organization, priesthood, and severe dogmas and instead nurtured the mystical and the benevolent. Blake believed that the human and the divine were one and the same, and that exercising the imagination was itself a spiritual act.

He earned a living primarily as an engraver.

Though today Blake is known as one of the “Big Six” English Romantic poets—along with William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and John Keats—his principal vocation during his lifetime was that of an engraver. Interested in art from a young age, he attended Henry Pars’s Drawing School on the Strand, where he learned how to draw the human figure from plaster casts. At the age of 14, he began a seven-year apprenticeship to James Basire, a conservative, somewhat old-fashioned commercial printmaker known for his architectural prints. With Basire, Blake picked up the the ins and outs of etching and engraving, from polishing copperplates to sharpening tools and coating plates with acid, and eventually etching plates himself. Aware of his apprentice’s talent, Basire sent Blake to Westminster Abbey, where he sketched medieval monuments in preparation for engraving. It was there, in the chapel’s ornate interior, Blake discovered his love for the Gothic.

In his free time, Blake purchased and engraved copies of cheap prints by Raphael, Michelangelo, Giulio Romano, and Albrecht Dürer, whose work he deeply admired. Blake also wanted to paint, yet his success was stifled by aesthetic tastes of the time. In 1779, he enrolled in the Royal Academy of the Arts, choosing watercolor as his medium and religious and historical scenes as his subjects, thus eschewing what were then-fashionable oil paintings of landscapes and portraits. Detesting the conservative teachings of the academy president, the portrait painter Sir Joshua Reynolds, Blake dropped out after just one year.

He invented an entirely new method of etching, which he used to create his “illuminated books.”

While making a living on commercial projects and commissions, Blake searched for a way to print and publish his own poems. Sometime around 1788, the answer came to him in a vision of his recently deceased brother, Robert, who revealed a new technique of “relief etching.”

Typically an intaglio process, etching involves incising a design into a copper plate covered with acid-resistant wax. When dipped in acid, the incised areas (unprotected by wax) are further eroded. When ink is applied to the entire plate and then wiped off, only the grooved portions are left containing ink. Pushed through a press, these designs create the final impression on paper.

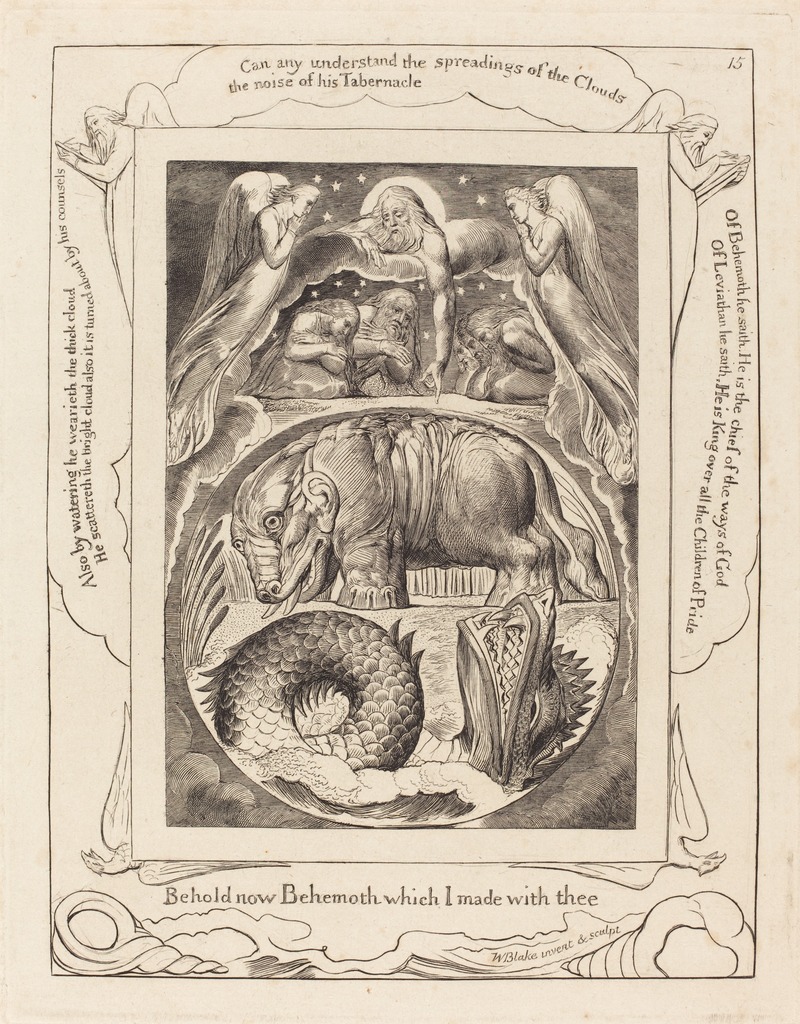

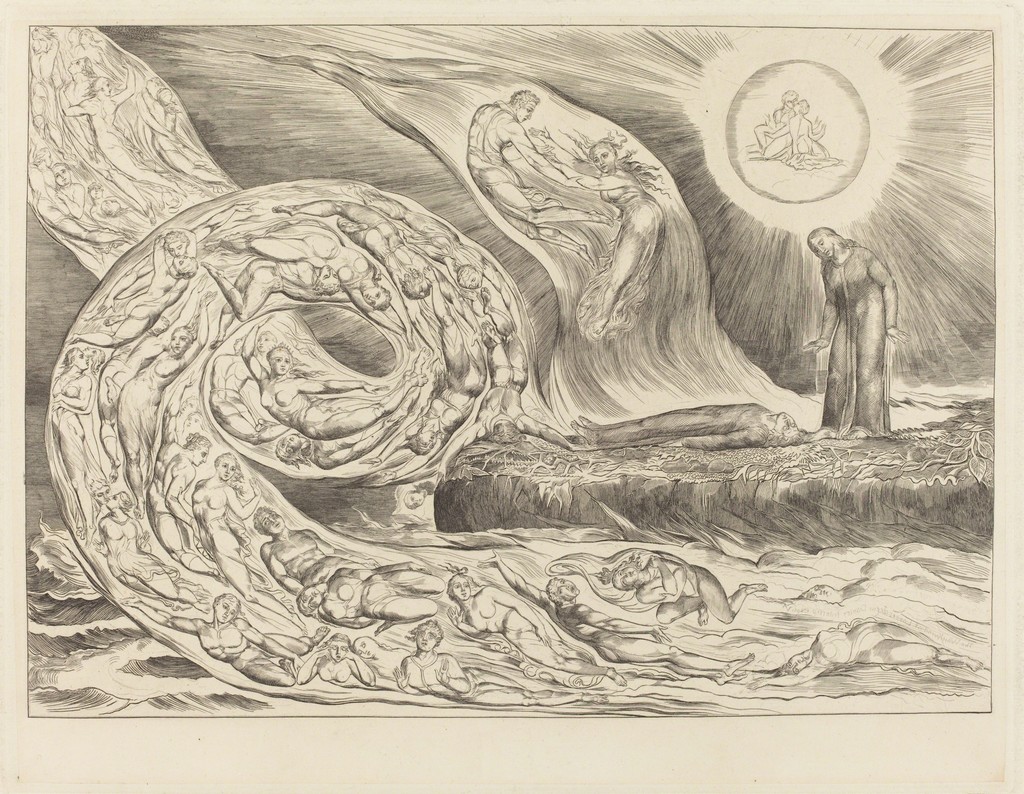

In his own method, Blake painted his designs on a copperplate with acid-resistant varnish; acid would then eat away at the untouched areas and leave only the design in relief. Ultimately, this technique allowed the artist to control all aspects of production, from writing the verses and designing the imagery to printing the plate, coloring in by hand if necessary, and bounding the pages in covers. The results were his “illuminated books.” Subjects ranged from prophecies (as in his 1790 “Continental Prophecies” of America and Europe) to religious and social satire (as in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell from 1790) with frequent comments on contemporary topics such as poverty, child labor, racial inequality, and the hypocrisy of the church. Blake even invented his own mythological cast of characters: There was Albion, the primeval man; Orc, the spirit of rebellion; and Urizen, the embodiment of reason and law who was dramatically depicted in one of Blake’s most celebrated prints, The Ancient of Days (1794).

He was little-known during his lifetime.

Considering Blake’s place in literature and art history today, it’s hard to believe he was unheralded in his own lifetime. Resolved to a life of simple pleasures—printmaking, poetry, and his loving wife and assistant, Catherine—Blake died poor, having achieved far less fame than his Romantic peers William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. In fact, when men originally sought to erect a memorial in his honor, they were unable to find the exact location of his grave. (A memorial was eventually erected, in 1957, in Westminster Abbey.) Only with the 1863 publication of Alexander Gilchrist’s biography The Life of William Blake, more than three decades after Blake’s his death, was he saved from oblivion and granted his due recognition in art and literature.

He has inspired songwriters, poets, authors, graphic novelists, and artists—from Jackson Pollock to Philip Pullman.

Rescued from obscurity by Gilchrist’s biography, Blake’s dreamlike scenes and verses influenced a range of artistic movements from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who shared his penchant for the Gothic, to Surrealism, whose followers admired Blake’s visionary transformations of the physical world. Even the Abstract Expressionist Jackson Pollock was said to have a fondness for the artist; he had one of Blake’s illustrations pinned to a wall in his Long Island studio.

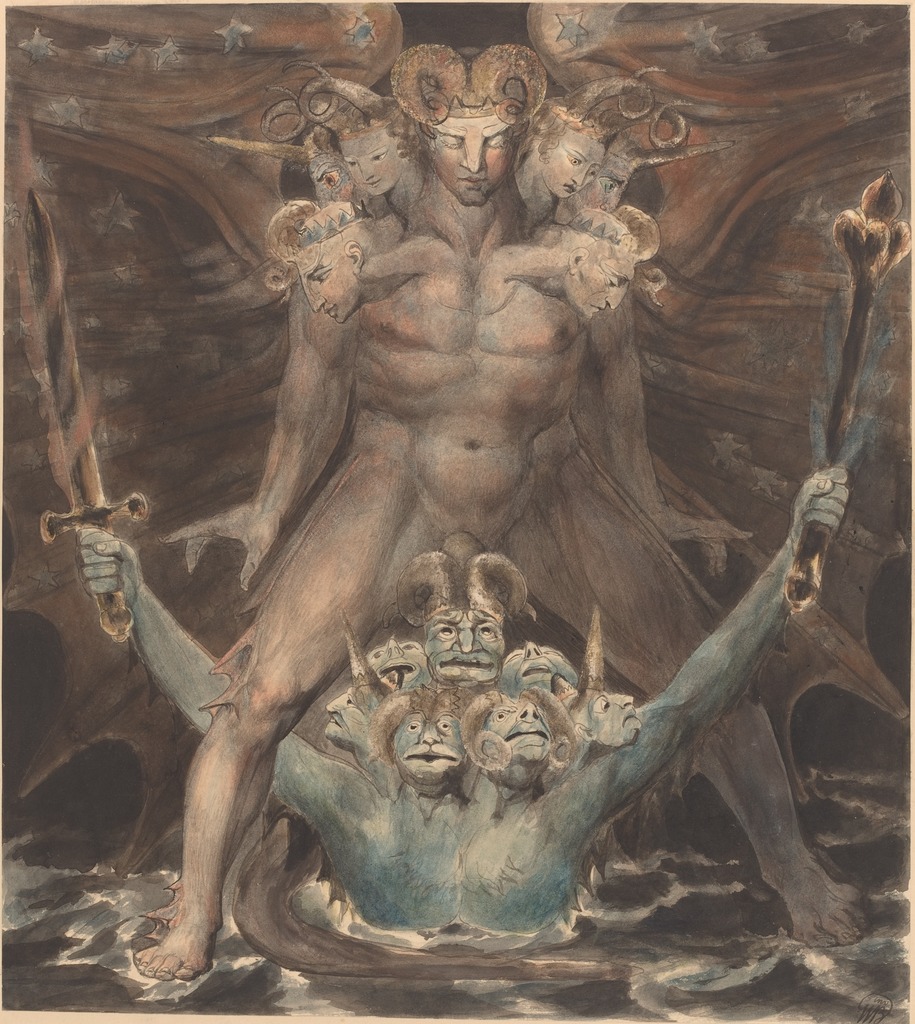

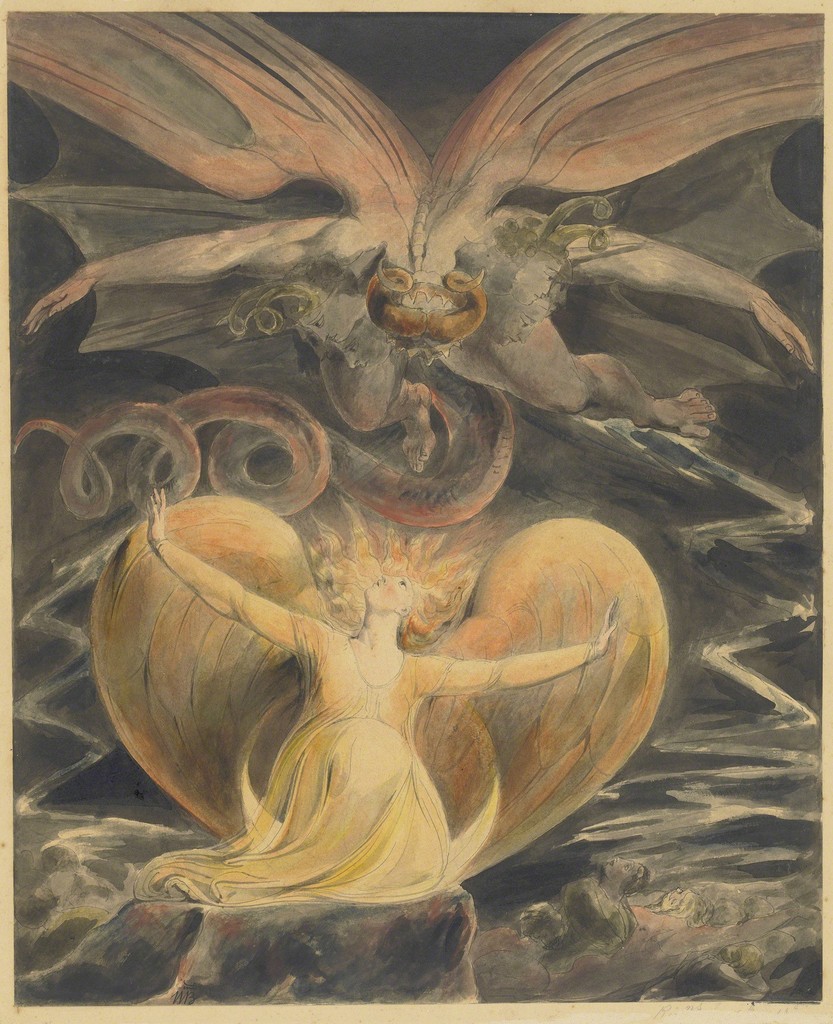

His influence has also been cited by novelists, poets, and songwriters, including James Joyce, Salman Rushdie, Allen Ginsberg, T.S. Eliot, Walt Whitman, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and Patti Smith. Given the otherworldly nature of his work, Blake’s influence on the fantasy genre is particularly compelling. Philip Pullman cited Blake, along with Milton and Heinrich von Kleist, as an inspiration for the “His Dark Materials” trilogy. Likewise, in the crime genre, Blake’s Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in Sun (1803–05) spurs the protagonist in Thomas Harris’s Red Dragon (1981) to murder two families in hopes of gaining the strength of the dragon in Blake’s painting.

Aside from incorporating Blake’s work in his graphic novels V for Vendetta (1982–85) and Watchmen (1986–87), Alan Moore featured Blake himself as a mystical character in From Hell (1991–98). Moore, another Englishman, said the artist “was living in a London which was not much more than a squalid horse toilet, on which he superimposed a magnificent four-fold city and populated it with angels, and philosophers of the past. Art at its best has the power to insist on a different reality.”

Blake indeed lived his own reality. Along with his radical beliefs, he was known to be excessively self-confident and stubborn, rejecting any opinions out of line with his own. It was likely this refusal to conform that buried him in obscurity during his lifetime—and, eventually, cemented him as a visionary hero and symbol of artistic individualism.

—Demie Kim

No comments:

Post a Comment